Ostrów Mazowiecka

“Alte Hejm”

The Old Country

Four Zionist Newspapers

The History of Ostrowa

By Arja Lejb Margolis, Tel-Aviv

Translated by Judie Ostroff Goldstein

For various reasons, Jews settled in Mazowsze [Mazovia] later than in other parts of Poland. The reasons being:

- The political independence of the realm with its own court and political traditions.

- Economic independence and strong opposition on the part of the Catholic Church.

Until 1526, Mazowsze was an independent duchy and the connection to the crown was weak, but the Mazowsze nobles recognized the Polish Kings and the government. By mid 14th century they swore loyalty to the Kings, but until 1526 they maintained their independence.

The Polish kings were able to incorporate Mazowsze into the crown in a process that began in the 15th century. Whenever a Mazowsze noble died without children, their land was incorporated into Greater Poland. In 1462 the districts of Rawa and Gostynim were incorporated in this manner. In 1464 – Sochachów and in 1495 Plock and Ostrowa. The largest part of Mazowsze Duchy was incorporated into the crown after the death of the last two dukes of the old Pyast dynasty died without heirs.

This happened in 1526. The area that was incorporated into the crown in 1526 was given wide autonomy and had their own judicial courts.

After 1526 the entire Mazowsze Duchy was divided into three provinces: Rawa, Plock and Czersk (Mazowsze). (ref. “Historja Polska”, 104 by S. Koczewy). In 1578 King Batory instituted the Polish judicial system in Mazowsze.

There were several attempts by the nobility, from the 15th through the 18th century, to pass a law expelling the Jews from Mazowsze, but none were successful.

We hear demands from all sides to expel the Jews from Mazowsze until the end of the 18th century. Even the “Council of the Four Lands” produced a rabbinical decree that no Jews should settle in Mazowsze. In 1669 the interdiction decrees from the “Council of the Four Lands” was read aloud in the Tikocyn synagogue. (Pinkus Tiktyn)

A law was passed by the King, beginning 28th March 1789 and in force until 1862, forbidding Jews from settling in Ostrów Mazowiecka. In 1856 the Jews were already a majority, two thousand four hundred ten Jews to one thousand five hundred sixty Christians.

I found this in the “Jewish Encyclopedia”, Petrograd, published by Efrun (volume 12, Pg. 28-147). Also from a population census in 1897, the number of inhabitants in the Ostrów district totaled ninety-eight thousand – seventeen thousand two hundred ninety were Jews. The population of Ostrowa itself was ten thousand four hundred seventy-one of which five thousand nine hundred sixty were Jews.

There were many attempts to keep the Jews out of Mazowsze by both Christians and Jews, however none of them were successful. The Jews continued to live in Mazowsze and spread out into all the cities and villages, including the Jewish community in Ostrowa.

Ostrów Mazowiecka, a district city, had belonged to Lomza Gubernia. The city is located on a flat, hill-less area that is the water table for the Narew and Bug rivers. The inlets from the two rivers flowed into the third, the Brok. (ref. Slownik Geographiczny).

Ostrów Mazowiecka was ninety-three versts from Warszawa, forty-one versts from Lomza, ninety versts from Bialystok, fifteen versts from Malkinia (railroad station on the line Warszawa-Petrograd) and ten versts from the Bug River.

A top grade, important highway goes through Ostrowa from Serock and Wyszków to Bialystok. There were not many rivers in the Ostrów District. (Neighbouring Ostroleka District was rich in water.) The middle area in the northern part of the district had no water. The southern and eastern parts have the Brok River with several inlets from the Bug River.

Almost the entire Ostrów District, starting from the historical era, was one large, first growth primeval forest, in which there were very sparse, scattered, small communities (colonies). Communities during the hunting age were in the forests around Brok. The principal for the city was the hunting-palace of the Dukes. The unproductive soil was not conducive to establishing a lot of colonies. This was not a good area for large agricultural endeavors. There were some middle-sized, but mainly small peasant holdings and there were only fifty-seven noble households.

In the realm of communications, Ostrów District, particularly the southern and eastern sections were well provided for.

The Bug River flowed at the southern border of the district. The railroad Warszawa-St. Petersburg cut through the southeastern portion of the district for thirty versts with stations in Malkinia Górna and Czyzewo.

The top-grade Bialystok highway cut through the district, for forty-three versts, from southwest to northeast. Another second-grade highway went through the district (through Ostrowa to Ostroleka) for twenty-eight versts. About the founding of Ostrowa, there is a version that states the city had royal privileges and the city had been established in 1410.

The Duke of Mazowiecka, Boleslaw IV, had given his village (Ostrowa) the privileges of a city in 1410. The Mazowiecka Princess Anny (when Poland gained independence the old market, called Rynek, was renamed “Plac Anny Mazowiecka”) never extended the privileges.

In 1930 (when I was a member of the city council) the city celebrated its 500th anniversary. The Mayor, Jan Zakszewski (who thought of himself as an historian) put out a brochure about the history of the city.

After the incorporation of Mazowiecka (into the Polish crown) the Polish kings confirmed the privileges of the city Ostrów Mazowiecka. According to a decision by the Sejm in 1565, Ostrów was united under one Governor.

In 1616 in back of the city was a royal court, where trials took place in matters concerning the villages and the city. At that time there were four hundred fifty-three houses in the city. Behind the city there was also a mulberry tree plantation (with a total of thirty thousand trees) run by A. Bogucki.

In 1660, Ostrowa together with surrounding villages had 5,509 inhabitants. An order from the King dated the 28th of March, 1789 (in effect until 1862) forbid Jews from settling in Ostrów Mazowiecka. In 1856 the Jews were already a majority with 2,410 Jews to 1,560 Christians.

In 1827 there were 184 houses and 1,792 inhabitants in the city and in 1860, 297 houses and 4,119 inhabitants (of which 2,486 were Jews).

The spreading Ostrów District became part of Lomza Gubernia that was established in 1867 with eight communities from the old Ostroleka District and two from Pultusk District.

There was already a railroad line to Warszawa in the district in 1867. There were 77,700 inhabitants in the District – by religion: 61,761 Catholics, 2,797Evangelists, 67 Protestants and 12,515 Jews. In Ostrowa there were two elementary schools and in the surrounding villages: Brok, Nur, Andrzejewo, Wasewo, Zambrów, Czyzewo, Dlugiosiodlo and Komorowo – only one school.

The Ostrów District was divided into twelve communities, in which there were four hundred twenty-six villages. Roads were built to Wyszków and Bialystok.

Six fairs a year were held in Ostrowa. There was a tobacco factory, a lot of windmills and a famous toilet water factory owned by the pharmacist and established in the pharmacy. Afterward, a hospital was built (Christian, not used by the Jews), a Post Office-Telegraph building, and government buildings for the civil servants.

In 1886 there were two schools (one for boys and one for girls), a Justice of the Peace for four districts, a district office, a City Hall, Post Office-Telegraph office. There were 472 houses (five were brick) with 7,800 inhabitants: 2,688 Catholics, 6 Protestants, 18 Evangelists and 5,088 Jews.

From the population census of 1897, the total number of inhabitants in Ostrów District was 98,000 of which 17,290 were Jews. In Ostrowa of 10,471 inhabitants, 5,660 were Jews.

Of all the villages in the district, these had more than five hundred inhabitants. Andrzejewo had 1,448 inhabitants (of which 586 were Jews). Brok had 2,657 (1,296 Jews). In Wasewo there were 576 (196 Jews). Dlugosiodlo numbered 1,249 Christians (800 Jews). Zareby Koscielne had 1,241 Christians and (1,063 Jews). Malkinia had 1,091 Christians (348 Jews). In Nur there were 2,133 Christians and (1,212). Poreba had 541 Christians (74 Jews); Suchcice 522 Christians (88 Jews) and Czyzewo 1,785 Christians (1,596 Jews).

At the end of the 19th century there were sixty-three windmills with a yearly output of 53,450 rubles, nineteen water mills with 6,620 rubles, Liquor Distilleries: in Branszczyk, Zoszków and Trynosy with an output of 88,500 rubles; Tobacco factory – 19,615 Rubles; Brewery – 7,500 Rubles. At the pharmacy there was a toilet water factory (famous throughout the country).

In the 20th century, thanks to Jewish initiative and organization, industries grew. The forest was a treasure. There were two sawmills in the city and forestry was the largest industry in town, as well as in the villages around Ostrowa. Lumber was sent to Warszawa and other cities far and wide, as well being exported to Germany and England.

Due to the large military presence in the city and in Komorowo, steams mills were built and had a large output especially the large mill “Automat”. With twenty-four pairs of rollers it was one of the largest in Poland and shipped product all over the country.

The brewery also increased its output and was known for its high quality beer that was also shipped to Warszawa. There were also some small manufacturing enterprises such as a glass factory, a vinegar factory, etc.

The Jewish population however did not grow because a lot of Jews had moved. A lot had left (especially the young ones) for the large cities, like Warszawa, Łódz, etc. An even larger number had emigrated to America, Argentina, Uruguay and other countries around the globe. Some of the young people had made aliyah.

In 1921, the population of the city was 13,425 of which 6,812 were Jews.

In 1934 (after Komorowo and other villages were incorporated into the city), there were 20,000 inhabitants of which 8.000 were Jews.

A Walk Through the City

By Arija Lejb Margolis, Tel-Aviv

Translated by Judie Ostroff Goldstein

In the eastern part of Poland, in Mazowsze, lies our town Ostrowa, whose name became Ostrów Mazowiecka. The city is surrounded by forests, depended upon for the past five hundred years. Back when people began to inhabit the city, there was one large forest that extended for many kilometers. Now roads stretch in many directions. First of all there is the highway from Warszawa which cuts through Radzymin, Wyszków, then goes through Ostrowa and continues on to Zambrów, Bialystok, Grodno, Wilno and as far as Peterburg [St. Petersburg].

Entering the city, off to the right, is the road to the village of Brok on the “Bug” and on the left stretches the road to Goworowo, Rózan-Maków-Pultusk.

Continuing through the city via the market, ahead on the right is the road to the railroad station Malkinia Górna, 15 kilometers from Ostrowa. On the left stretches the road over to Komorowo village - 3 kilometers from Ostrowa, which continues to Ostroleka and as far as the German border.

The highway then goes over to Zambrów (30 kilometers from Ostrowa), to various other villages and on to Bialystok.

From ulica Ostrolecka turn off to ulica Lubiejewska (once called ulica Kosa) which is the road to the railroad station Siedlce-Lomza (which is located three kilometers from the city) and then the road over to Sniadowo and on to Lomza, fifty kilometers from Ostrowa.

Around Ostrowa are the small villages Wasewo, Poreba, Czerwin, Nur, Sterdyn, Brok, Dlugosiodlo, Andrzejewo, Zareby Koscielne and Czyzewo; whose merchants buy and sell in Ostrowa, the same as in scores of Prince's estates such as Biel, Ligiawe, Trynosy, and Kalinowo. There are also hundreds of large and small villages from which the peasants bring their products to sell and then to buy the goods they need for their farms and homes. The market was held every Monday and Thursday; once a month (Monday) was the Monthly Fair; four times a year – there was what people called the “Year-Fair”.

The grain trade was a major industry, as there were several steam-mills; the main one being the large mill “automat”. Also the lumber trade played a major role in our livelihood. There were two large sawmills: one belonged to Zelman Jozef Nutkiewicz and the other to the family of the late Hirszel Tejtel. Forestry was important. But in Poland the wood was sent to foreign countries to become various materials. Grain and wood actually were the two main industries providing employment in the city.

In the centre of the city lies the old marketplace where the City Hall now stands, built 1925 to 1927, in the Kraków style with a tower and a clock on all four sides. The City Hall was used for town council sessions. The city committee (subordinate to the town council) which managed the city affairs met there as well. The town council and committee were chosen every five years.

In former times, before the First World War (1914 -1918), Jews had no influence over decisions made at City Hall. The city President managed the city himself, asking nothing of anyone and in charge of everybody. The Jews struggled to pay high taxes and had no say in the matter.

|

|

Tejtel family sawmill |

During the German occupation, there was a small change for the better. There was a Jewish Vice-Mayor (Hirszel Tejtel) as well as some Jewish officials (Icchok Morgensztern, Kaplański and others).

During the era of Russian rule, Shamas Natan Zelig and Shamas Hirszel Balbier - called “szkolnik” [Polish, “teacher”], were often at City Hall as they registered the marriage and birth acts in the municipal record books. And at times the books were not in order. Some births had not been registered, or had been registered late. Later these irregularities created confusion when boys were asked to report to the military committee (conscription). Since the names in the register were not correct, the committee was not always able to determine who should report for the draft. An “expert” at doing this was Shamas Hirszel.

Around the four sides of the marketplace stood low wooden houses, in ones and twos. All the businesses in the market, wholesale and retail, were Jewish: food, iron, fashion goods, leather, haberdashery, kerosene, paint, food products - a to z.; as it had been for hundreds of years.

In the last years between the two world wars, the Christians had already opened businesses in the city. The Christian owners competed with the Jews, not by lowering prices, but by inciting the Christian population to boycott the Jewish merchants.

The entire life of the city was concentrated around the old marketplace. The streets branching off from the market were: Warszawer, 3go Maja, Pułtuska, Nurski, Malkińska, Solna, Jatkowa and the streets that joined with ulica Ostrołęcka to Komorowo.

Streets run between the wooden houses, here and there a brick house, straight and crooked, the length and breadth of the entire city as far as the fields, forests and highways which connect with other cities and villages. Narrow and wide streets connect street with street in the city itself.

The Jewish quarter exists first from the Old Market (as far back as the uprising in Poland named “Plac Kzienznej Anny Mazowieckiej”) and also the streets: Warszawska, Brokowska, Chausée Brokowska, Miodowa, Pułtuska, Rożanska, Koza (or Mieckiewicz), Jagielońska, Nurski, Solna, Ostrołęcka, Jatkowa and Batorego. Mixed streets were ulica 3go Maja, Malkińska, Pocztowa, Kosciuszki Alley, Ugniewska, Cmentarza, Lubiejewska and the Piaskes. Clean gentile streets were away from the centre– around the outskirts of the city, with their own gardens and orchards.

|

|

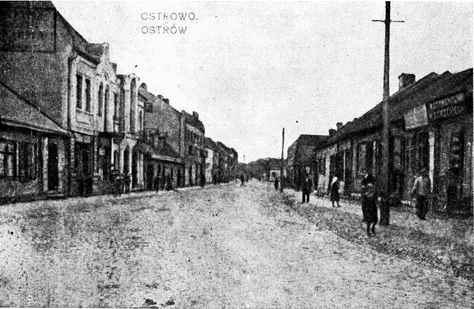

Warszawska Street |

|

|

ulica 3go Maja |

|

|

Pocztowa Street |

|

|

|

At each of the corners (four) of the marketplace there was a water-pump (four in all) where people went to get “hard” water for use in the house and for livestock. The pumps squeaked and groaned each time the curved handle went up. In winter there was usually a pile of ice around the pumps that hampered access. Often the water carrier had to put down burning pieces of wood to melt the ice.

“Soft water” or “tea water” from the wodoczong [water pump] was also available at the old market. The water carrier used to deliver water from house to house. Crazy Icchok carried water for many years. He believed that he was an Emperor with his own militia (In summer when the military would leave the city to go on maneuvers, he deserted his pails and went off with the military, carrying a pack on his shoulder like a rifle. The officers already knew him and did not interfere). Szepsel wasertreger [water carrier] was also popular. Later, a fire hut [fire station] was put up near the wodoczong. (In 1925 during the building of the city hall, the wodoczong and the fire hut were removed).

Besides being large and small wood and grain merchants, Jews were: buyers, sellers, re-sellers, brokers, wagon drivers, porters, craftsmen and old clothes peddlers at the fairs here in town and away from home.

The “rulers” of the small market were the fish, fruit and vegetable merchants, for whom the housewives would tremble with fear and if not careful were taken in “by their big mouths”. During the winter, the merchants' wives wore warm coats, padded with soft cotton, sat on top of the stalls, kegs and baskets with a pot of glowing coals between their knees to stay warm.

Fish was delivered in wooden “berths” and fruits in small wooden barrels or round, deep baskets. Spread out over the wooden stalls were red and yellow cherries, green gooseberries, rosy red-berries, plums of all kinds, large apples, pears, black radish, red radish, yellow carrots, onions, beets, fruits and vegetables - all to delight the eye with cool, fresh produce. The small market was full, even in the weeks before the arrival of Yontef.

The streets were paved with round fieldstones (cobblestones), pressed together and wild grass grew between the stones.

In latter years, along Warszawska (later Pilsudskiego) and 3go Maja (formerly Przedmieszcze) there were sidewalks made of cement slabs only on one side of the street. In the lanes there were none; only a deep gutter where a gully, divided by pointed stones, kept the rainwater in the gutter. Young boys took off their boots and socks and waded in the water, which froze in winter

|

|

Two young, heder boys |

and became a slide. Trees were found only on the Christian streets. The Jewish shtetl consisted of a lot of wooden houses, a few brick houses [covered with stucco], narrow lanes, open courtyards used as public access to get from street to street, narrow footpaths and inner courtyards. They told about a poor, unassuming, but respectful life; a partnership between house and house, courtyard and courtyard. Despite their forlorn appearance, every street had its own way of life, local colour and history.

Standing between Warszawska and Brokowska highways, at the Russian Orthodox Church, is a water pump; opposite the water pump is the white brick house of the Jewish doctor Kliaczke (during Word War One, 1914-1918 he was exiled to Russia), which was later used by the cultural society and public library.

On the other side of the Orthodox Church was the Promenade Garden (that the Poles called Napoleon Square) During the day the children played there and at night - couples in love.

On Sunday the bells from the Orthodox Church called people to prayer. From the other corner of the city, on ulica 3go Maja, the Catholic Church did the same and they competed with each other to see which would overpower the other with their bim-bom, bim-bom.

A new era arrived. The Poles took some land from the Orthodox Church and added it to the promenade-garden.

Further along ulica Warszawska, past the brewery was the sadzawka. Who does not remember the sadzawka from childhood, the natural pond where children caught small fish. Also, during the summer, the elders would rest in the shade of the beautiful trees and in winter, there were skaters on the frozen pond.

Past the sadzawka is the house of Abram Icchok Frejman. He supplied meat to the Polish military in Komorowo and other towns.

Next to it - the home of the big lumber merchant, Jozef Froimowicz, partner in his father-in-law's sawmill. Opposite right - the building of the Governor in Ostrowa - and its garden - one of the prettiest in the city. Only the garden separated the 2 roads: the one on the right, the Warszawska Highway, via Wyszków and Radzymin. The forest runs the entire length of the road. There one rented summer cottages and also strolled; on the left - the highway to Brok, ten kilometers from Ostrowa. The entire road - full of woods where most people strolled and on Shabes the poor craftsmen and workers came to rest with their families. These woods could tell many tales from the romantic era.